“I repose in this quiet and secluded spot, not from any natural preference for solitude, but finding other cemeteries limited as to race, by charter rules, I have chosen this that I might illustrate in my death the principles which I advocated through a long life, equality of man before his Creator.

Inscription on the Tombstone of Thaddeus Stevens

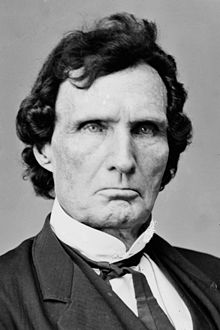

As regular readers of this blog know, I greatly enjoyed the film Lincoln and praised it for its overall historical accuracy. Go here to read my review. One of the many aspects of the film that I appreciated was Tommy Lee Jones’ portrayal of Thaddeus Stevens (R.Pa.), a radical Republican who rose from poverty to become the leader of the abolitionists in the House, and one of the most powerful men in the country from 1861 to his death in 1868. There haven’t been many screen portrayals of Stevens, but they illustrate how perceptions of Stevens have shifted based upon perceptions of Reconstruction and civil rights for blacks.

The above is an excellent video on the subject.

The 1915 film Birth of a Nation, has a barely concealed portrayal of Stevens under the name of Congressman Austin Stoneman, the white mentor of mulatto Silas Lynch, the villain of the film, who makes himself virtual dictator of South Carolina until he is toppled by heroic Klansmen. The film was in line with the Lost Cause mythology that portrayed Reconstruction as a tragic crime that imposed governments made up of ignorant blacks and scheming Yankee carpetbaggers upon the South. This was the predominant view of scholarly opinion at the time. The film was attacked by both the NAACP and the Grand Army of the Republic, the Union veterans’ organization, as being untrue to history, a glorification of mob violence and racist.

By 1942 when the film Tennessee Johnson was made, we see a substantial shift in the portrayal of Stevens. Played by veteran actor Lionel Barrymore, best know today for his portrayal of Mr. Potter in It’s a Wonderful Life, Stevens is portrayed as a fanatic out to punish the South and fearful that the too lenient, in his view, treatment of the South in Reconstruction will lead to a new Civil War. This leads up to the climax of the film, the trial in the Senate of Johnson, with Stevens as the leader of the House delegation prosecuting Johnson, with Johnson staying in office by one vote. The portrayal of Stevens is not one-dimensional. Stevens is shown as basically a good, if curmudgeonly, man, consumed by fears of a new Civil War and wishing to help the newly emancipated slaves, albeit wrong in his desire to punish the South. Like Birth of a Nation, Tennessee Johnson reflected the scholarly consensus of the day which still painted Reconstruction in a negative light, although not as negative as in 1915. Additionally, the issue of contemporary civil rights for blacks was beginning to emerge outside of the black community as an issue, and Stevens in the film is not attacked on his insistence for civil rights for blacks.

Tommy Lee Jones in Lincoln gives a masterful performance as Stevens. As indicated in the above video he had, to say the least, a prickly relationship with the Lincoln administration as Chairman of the Ways and Means Committee, then as now one of the most powerful posts in the House. Like most abolitionists Stevens viewed the Lincoln administration as laggard in its anti-slavery measures, and if Lincoln had not been assassinated no doubt Reconstruction policy would have featured numerous battles between Lincoln and Stevens. The Lincoln film can be viewed as a tribute to two men: Stevens and Lincoln, which would no doubt have vastly amused both men who so often clashed in life. Contemporary scholarship almost entirely views Reconstruction as the noblest of experiments foiled by racists North and South and the issue of race today is the prism by which most scholars view the past, not unusual for viewing the Civil War and Reconstruction, but usually reaching polar opposite conclusions of most scholars of the period from 1890 to 1955.

How we view our past always is always heavily influenced by present day conditions and the portrayal of Stevens in film is a striking example of that fact.

I saw “Lincoln” with my liberal in-laws.

This thought kept running through my alleged mind every time Stevens was on screen, “Alinsky’s Rule 5: ridicule.”

The movie didn’t change my opinion of Lincoln, one way or the other. I was impressed that I could sit through the whole of it: not much bang-bang, bloodshed or walking trees, etc.

It is one of the best films for showing the nuts and bolts of political horestrading that I have ever seen T.Shaw, and I, of course, found it fascinating for beginning to end. I have seen it twice now, something I have never done with any film while it was still in theaters.

T. Shaw I imagine you appreciate this line voiced by Stevens in the movie:

“The modern travesty of Thomas Jefferson’s political organization to which you have attached yourself like a barnacle has the effrontery to call itself “Democratic”. You are a Dem-o-crat! What’s the matter with you? Are you wicked?”

Mac,

That depends on how you define the word, “appreciate.”

I think the seed of that “barnacle” was attached by Jackson. Politics and rhetoric are not my areas of expertise. I have a talent for flinging massive strings of four-letter words.

Historians often unconsciously reveal more about their own times than the periods they describe, Gibbon and Macaulay, being obvious examples.

PLOT SPOILER ALERT: I thought the bedroom scene with Stevens and his mistress/housekeeper was manipulatively gratuitous. His intimate relationship with his housekeeper was based on rumor. It would not be surprising if there was a romance going on, but rumors of one sort or another would of course fly anyway, given that he was single. What bothered me was that, by introducing this love interest, Stevens went from a man who opposed slavery on principle to one who may have been acting under the emotional influence of someone in his household.