One of the hardest tasks at understanding the past is that History looks at the past like witches say their prayers: Backwards. A prime example of this is the Gettysburg Address. We look at it in the light of a Civil War won by the Union, a successfully restored nation and a Lincoln raised to mythic status. One hundred and fifty-seven years ago the war seemed like a failure for the Union to many observers, a struggle over a divided United States that was never going to be reunited, and Lincoln was viewed by many of his friends, as well as his foes, as a small time politician who mysteriously lucked into the White House, who was manifestly way over his head and who was destined to be remembered as a one term President who had the misfortune to preside over the permanent division into two nations of the old United States.

No doubt Lincoln understood these observations, and might even have privately agreed with the likelihood of the War ending with his defeat in 1864. The War in the East, well, the best that could be said is that Union victory at Gettysburg, mostly due to Confederate errors, preserved the status quo, which was a stalemate in Virginia which was disastrous for the Union. General Meade was a major disappointment to Lincoln, and would soon demonstrate, in the Mine Run Campaign of November 27, 1863-December 2, 1863, that he was a vastly inferior general to Lee, who simply was not going to be able to take the offensive and successfully crush the Army of Northern Virginia, even when he heavily outnumbered Lee, who had dispatched one-third of his Army, Longstreet’s Corps, to help out in the West.

The War in the West was going much better for the Union, but it had taken over two years for the Union to clear the Mississippi and conquer Tennessee.

Lincoln had under a year before the next Presidential election, and if the War continued as it had continued, he would lose his re-election and the War would end in two separate nations as successor states of the Old United States. The draft riot in New York City, put down by troops fresh from the battle of Gettysburg, was an ominous sign of the war weariness eating away at Northern morale. Unless Lincoln could demonstrate that the War was as good as won by election day in November 1864, it would be lost.

That was the nightmare that Lincoln confronted on November 19, 1863, and the Gettysburg Address was a small portion of his attempt to avert this from happening.

We are not really sure what Lincoln said. There are two drafts of the speech in Lincoln’s hand, and they differ from each other. It is quite likely that neither reflects precisely the words that Lincoln used in the Gettysburg Address. For the sake of simplicity, and because it is the version people usually think of when reference is made to the Gettysburg address, the text used here is the version carved on the walls of the Lincoln Memorial.

Fourscore and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal. Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle- field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field as a final resting-place for those who here gave their lives that this nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this. But, in a larger sense, we cannot dedicate…we cannot consecrate…we cannot hallow…this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us, the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us…that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion; that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain; that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom; and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

Here was the masterpiece of Lincoln’s passion for concise, almost terse, argument. No doubt many in the audience were amazed when Lincoln sat down, probably assuming that this was a preamble to his main speech.

“Fourscore and seven years ago”

Lincoln starts out with an attention grabber. Rather than the prosaic eighty-seven years, he treats his listeners to a poetic line that causes them to think and follow Lincoln back in time to the founding.

“our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation,”

Not an alliance, but a new nation, brought forth by the founding fathers, the fount of Lincoln’s political philosophy.

“and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal”

Here we have the heart of Lincoln’s lifelong abhorrence and battle against slavery, and against those who attacked the phrase “that all men are created equal” in the Declaration. In this letter to Joshua Speed in 1855 he summed up his fear that the nation was falling away from this basic truth of the founding: “Our progress in degeneracy appears to me to be pretty rapid. As a nation, we began by declaring that “all men are created equal.” We now practically read it “all men are created equal, except negroes” When the Know—Nothings get control, it will read “all men are created equal, except negroes, and foreigners, and Catholics.” When it comes to this I should prefer emigrating to some country where they make no pretence of loving liberty —— to Russia, for instance, where despotism can be taken pure, and without the base alloy of hypocracy [sic]. “

In the Dred Scott decision Chief Justice Taney stated his belief that the opinion of whites was more favorable to the negro in the 1850s than it was in 1776. Lincoln ridiculed this opinion:

Lincoln was more correct than he knew. Traditional racism was receiving reinforcement from “scientific racism”, the putrid fruits of which were seen during the era of Jim Crow after the Civil War, and enshrined in most of our more prestigious colleges. I have a book in my private library entitled Reconstruction and the Constitution by John W. Burgess, Dean of the Department of Political Science at Columbia University, and published in 1902. Burgess, a Union veteran, was one of the founders of political science as an academic discipline in this country. He states baldly throughout the book that blacks are an inferior race and that this was the prime error of Reconstruction in attempting to place political power in the hands of a race manifestly unable to wield it wisely. While deploring the violence of whites against blacks during and after Reconstruction, he regards the political subjugation of the blacks as the natural order of things. On page 298 he has this chilling sentence: “The white men of the South need now have no further fear that the Republican party, or Republican Administrations, will ever again give themselves over to the vain imagination of the political equality of man.” Well educated racism of this type, fortunately, never reached the nadir in this country that was reached in Europe in the forties of the last century. Lincoln and his anti-slavery colleagues were fighting against not just bigotry but a strong intellectual tide that was very much against the basic equality of man set forth in Mr. Jefferson’s immortal phrase. Who can say what bleaker path our history may have taken if Lincoln’s attempt to defend the proposition that all men are created equal had been forgotten in the aftermath of defeat for the Union and the creation of a new American nation dedicated to the proposition that all men are not created equal.

“Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure.”

Republics had proven themselves fragile things since 1776. The Latin American republics had entered into their disheartening dance of republics punctuated by dictatorships and chaos. France after two attempts at being a republic was a Napoleonic empire again. Now the great American republic, the beacon light of free institutions, was shattered by civil war. Whether republicanism was a viable form of government was very much in doubt in 1863.

“We are met on a great battle-field of that war.”

And a great Union victory, the only great victory the Union had thus far attained over Robert E. Lee and his hitherto well-nigh invincible Army of Northern Virginia. No wonder that Lincoln was willing to take time to visit this battlefield.

“We have come to dedicate a portion of that field as a final resting-place for those who here gave their lives that this nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we cannot dedicate…we cannot consecrate…we cannot hallow…this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it far above our poor power to add or detract.”

Lincoln here shifts the focus from the ceremony to the battle and the soldiers who fought it. He views their sacrifice as the consecration of the ground, and not the words he, or anyone else, says after the battle. Lincoln had read the Bible many times, and he knew that in both the Old and New Testaments it is the blood of victims that sanctifies. Note how Lincoln does not limit his last sentence to the Union soldiers.

“The world will little note nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here.”

This was a safe bet on Lincoln’s part since speeches by politicians are ephemeral in nature and Gettysburg was the biggest battle of the war. He would have been astonished and saddened if told that 157 years later the Gettysburg address is the one speech by a president that most Americans have heard of, while the details of the battle itself grow dimmer in the public mind as the years roll by.

“It is for us, the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced.”

Lincoln skillfully shifts from a remembrance of the dead to a clarion call to finish the war, the whole practical purpose of the address.

“It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us…that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion;”

The last full measure of devotion. Amazing that someone in as prosaic a profession as the law could have so much of the poet about him.

“that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain;”

Lincoln here addresses the nightmare that haunted both North and South throughout the Civil War: “After so much pain, suffering and death, what if my side loses?”

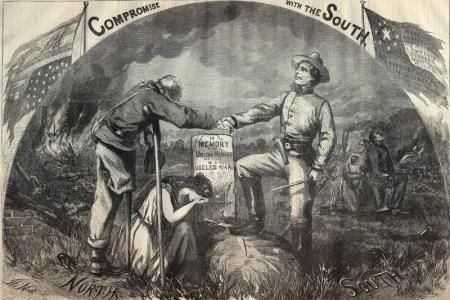

This pro-Lincoln illustration played upon this theme during the election campaign in 1864 where a crippled Union soldier shakes hands with a victorious Confederate soldier across a symbolic grave for the Union war dead killed in a useless war. Lady Liberty is weeping by the grave. To the right a Union black soldier and his wife and child, abandoned to re-enslavement, are shackled and weeping.

“that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom;”

What Lincoln meant by the phrase “under God” is open to conjecture. Reading it together with the Second Inaugural I believe that Lincoln was stating that if God willed it that the nation would pass through its terrible trial. A new birth of freedom is clear enough. The nation needed to embrace again the revolutionary faith embodied in the Declaration of Independence, Lincoln thus connecting the current struggle with the American Revolution, a holy cause in the eyes of most Americans in 1863, rather than the confused and divisive conflict that it was in 1775-1783.

“and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

Lincoln viewed our experiment in Democracy as something that could “perish from the earth”. In one of his earliest public addresses on January 27, 1838 Lincoln stated his fear that free government in America could die of suicide.

“How then shall we perform it?–At what point shall we expect the approach of danger? By what means shall we fortify against it?– Shall we expect some transatlantic military giant, to step the Ocean, and crush us at a blow? Never!–All the armies of Europe, Asia and Africa combined, with all the treasure of the earth (our own excepted) in their military chest; with a Buonaparte for a commander, could not by force, take a drink from the Ohio, or make a track on the Blue Ridge, in a trial of a thousand years.

At what point then is the approach of danger to be expected? I answer, if it ever reach us, it must spring up amongst us. It cannot come from abroad. If destruction be our lot, we must ourselves be its author and finisher. As a nation of freemen, we must live through all time, or die by suicide.”

Thus Lincoln was telling his audience and the nation that all the blood and misery was worth it and that they must win the war.

What Lincoln said was quite true in his time and is just as true in our time. Every generation of Americans determines through their actions whether “government of the people, by the people and for the people shall not perish from the earth.”

Laughton was an international treasure. Loved him in Spartacus.

You bring up a good point. A republic has to have its values and practices faithfully transmitted from one generation to another. The Preamble to the United States Constitution clearly refers to Posterity. The left in particular acts like the Constitution is something that they can do with as they please, with no responsibility to any other generation of Americans. Abortion makes this explicit. We seem to be losing the idea of things that are held as an intergenerational trust.

Agreed:

He gave a riveting performance in Advice and Consent as he was in the process of dying from renal cancer.